Amidst the churches, we saw a lot of other interesting sites, which spanned a huge range of historical and cultural events in German history.

Eisenach– One of the non-church UNESCO sites were visited was the Wartburg Castle in Eisenach. The first version of this hill-top residence was built in 1067 by Ludwig the Jumper.

Wartburg served as host to many important people, including St. Elizabeth of Hungary and Martin Luther after his excommunication. In this tiny room he translated the New Testament into German and developed what was to become the content of many of my nightmares….Hochdeutsch! (just kidding….but only a little!)

The concert hall in the castle is also where the first group of students gathered to protest and fight for a united Germany back in 1817.

Weimar – Home of Goethe, Bach, the Weimar Republic, Bauhaus, and numerous more…Weimar packs a historical punch of big names and UNESCO importance. In the Deutsches Nationaltheater, Germany’s first post-WWI Constitution was drafted, passed, and signed in 1919. It was a very hopeful time in Germany…if only it would have worked.

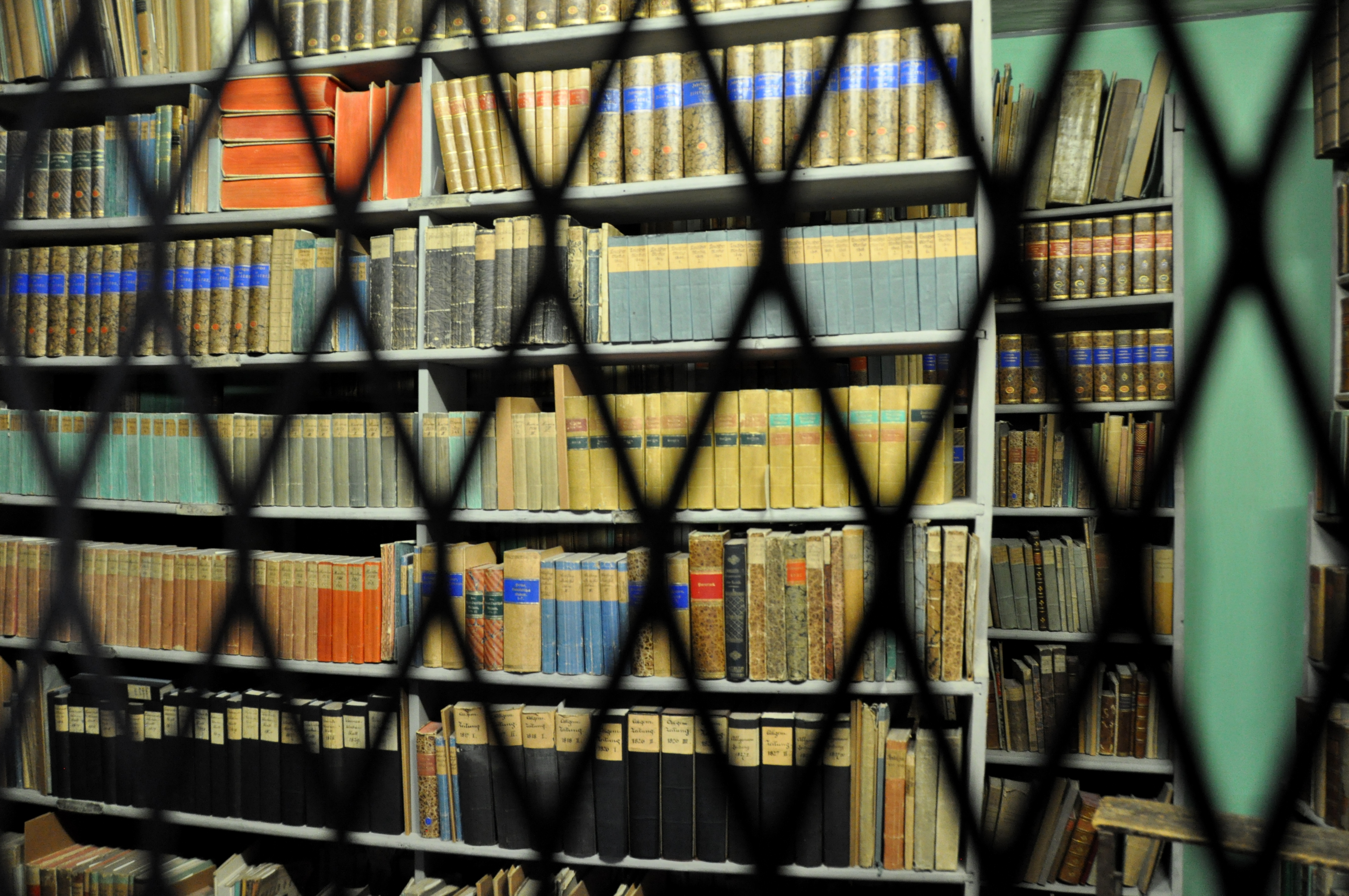

We visited the house where Goethe spent the last 50 years of his life and penned his most important and influential works, including Faust. The study and bedroom where Goethe died are preserved in their almost-original state. His books are kept behind lock and key and a museum attendant stands watch over them as visitors stroll past.

As we were walking through Goethe Nationalmuseum, which contains a lot of Goethe’s possessions, we saw this portrait of him. Joe calls me over and says, “Hey, look. Goethe invented the Snuggie too!”

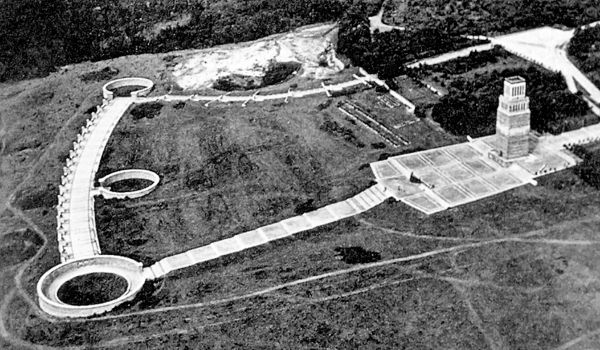

Buchenwald – Just outside of Weimar is the Buchenwald Memorial and Concentration Camp, one of the largest camps of its kind at the time. The Memorial entails a statue of prisoners awaiting liberation, a bell tower, and the “Avenue of the Nations” which honors victims from 18 different countries. I took this picture from the Stiftung Gedenkstätten Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora website, just to show how large the memorial grounds are. The view from the memorial was beautiful, as it deserves to be.

Buchenwald was liberated by the Third U.S. Army on April 11, 1945 at 3:15pm. The clock on the camp gate commemorates this exact time and the roman numerals on the Memorial Bellow Tower read “1945”.

President Obama visited Buchenwald on April 11, 2010 to celebrate the 65th anniversary of the liberation. He stood in front of the gate with Angela Merkel (German Bundeskanzlerin) and spoke of the “human capacity for good.” The capacity for horror at a Concentration Camp goes without saying, especially at Buchenwald. Here, a “Kinderblock” housed over 1000 children within the camp fences. Children at a concentration camp; I can’t think of anything worse. However, after visiting such a tragic place in this country’s – and this world’s – history, one has to search for the capacity for good, in order to maintain belief in the human race.

The “human capacity for good” was there, even in a concentration camp, during the darkest of days. There were people, officers, soldiers, Germans who didn’t believe in the “Final Solution”. Thankfully, many of them were at the Kinderblock. The children were housed in an area within Buchenwald called the “Little Camp”. It was also referred to as the “death zone” because disease was rampant, food was scarce, the conditions were worse than any other area of the camp, and prisoners were sent there to die. The unfortunate events that resulted in children being placed in this section of the camp actually saved hundreds of their lives. Lead officers rarely accessed the “Little Camp”, for fear of putting their own heath in danger, thus allowing the children to be protected. They were sheltered from hard manual labor, extra food was snuck into their barracks, and many of them safely avoided the twice daily roll call on the muster grounds. When the camp was liberated, hundreds of children were still alive.

Back then, they would be called traitors, but today, a group of un-named individuals with a deep “human capacity for good” are considered heroes.

The first ever memorial dedicated to the Sinti and Romany victims of WWII, gate and clock tower marking 3:15pm in the background.

Bonn – Speaking of children, a small section of the Haus der Geschichte museum focused on children after WWII and was really interesting. I think this has been one of the most interesting museums I have visited during this Olmsted experience. It chronicles the history of Germany from 1945 up to the present day. There was even a special exhibit on the relationship between Germany and the United States. I wish I could recommend it to anyone visiting Germany, but there is exceptionally little print material in English.

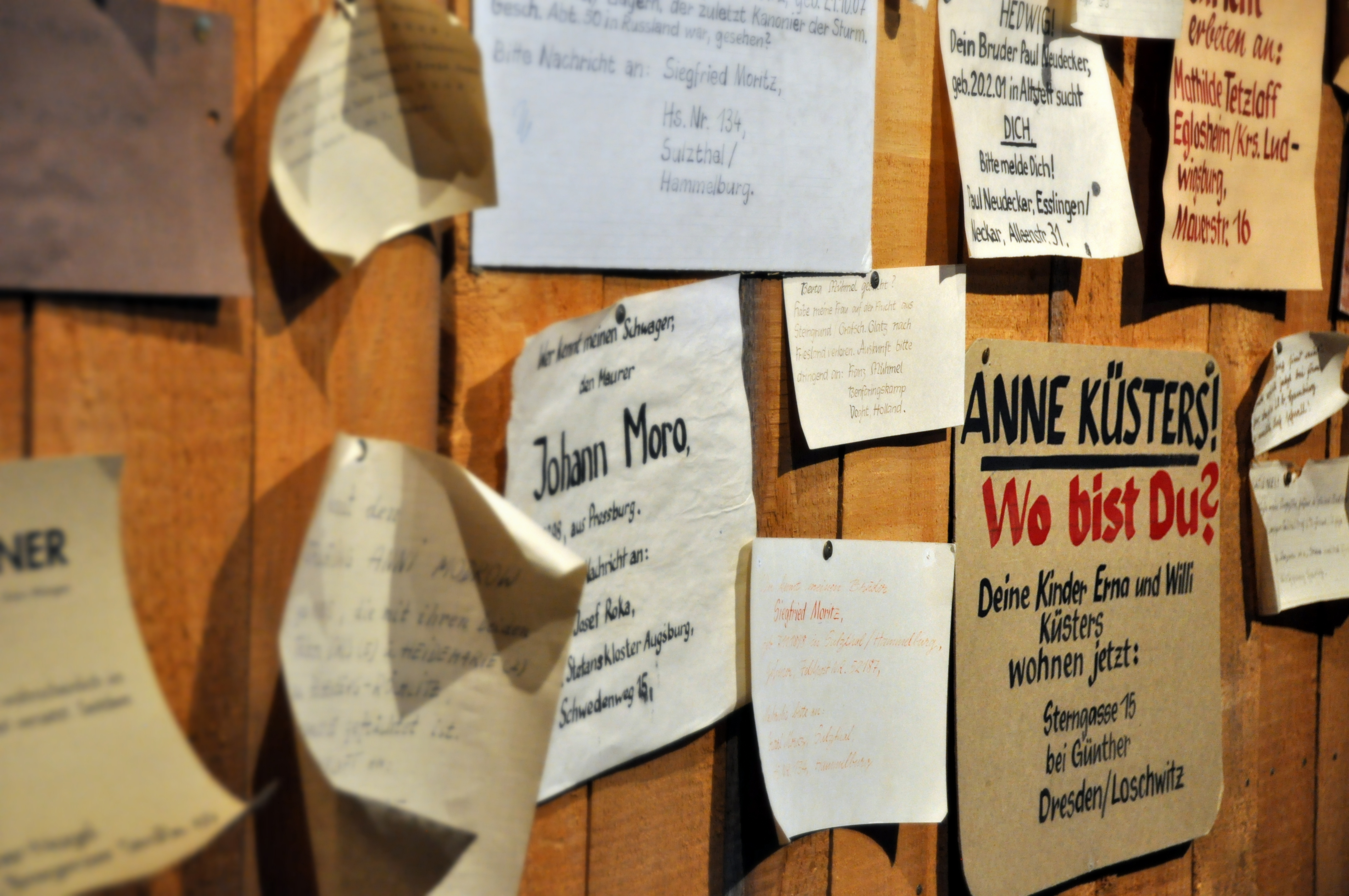

The point being how children, left orphaned, displaced, or just plain lost, were reunited with family after WWII. Every fourth person was searching for a relative at the end of 1945. Families hung posters, thousands of them, searching for information regarding the children. The search agencies (mainly churches and the German Red Cross) issued informational pamphlets, providing instructions for those missing and those searching. For example, individuals were discouraged from traveling from city to city, searching for loved ones. In the age before cell phones, no one could be contacted if they weren’t home, when information needed to be passed on.

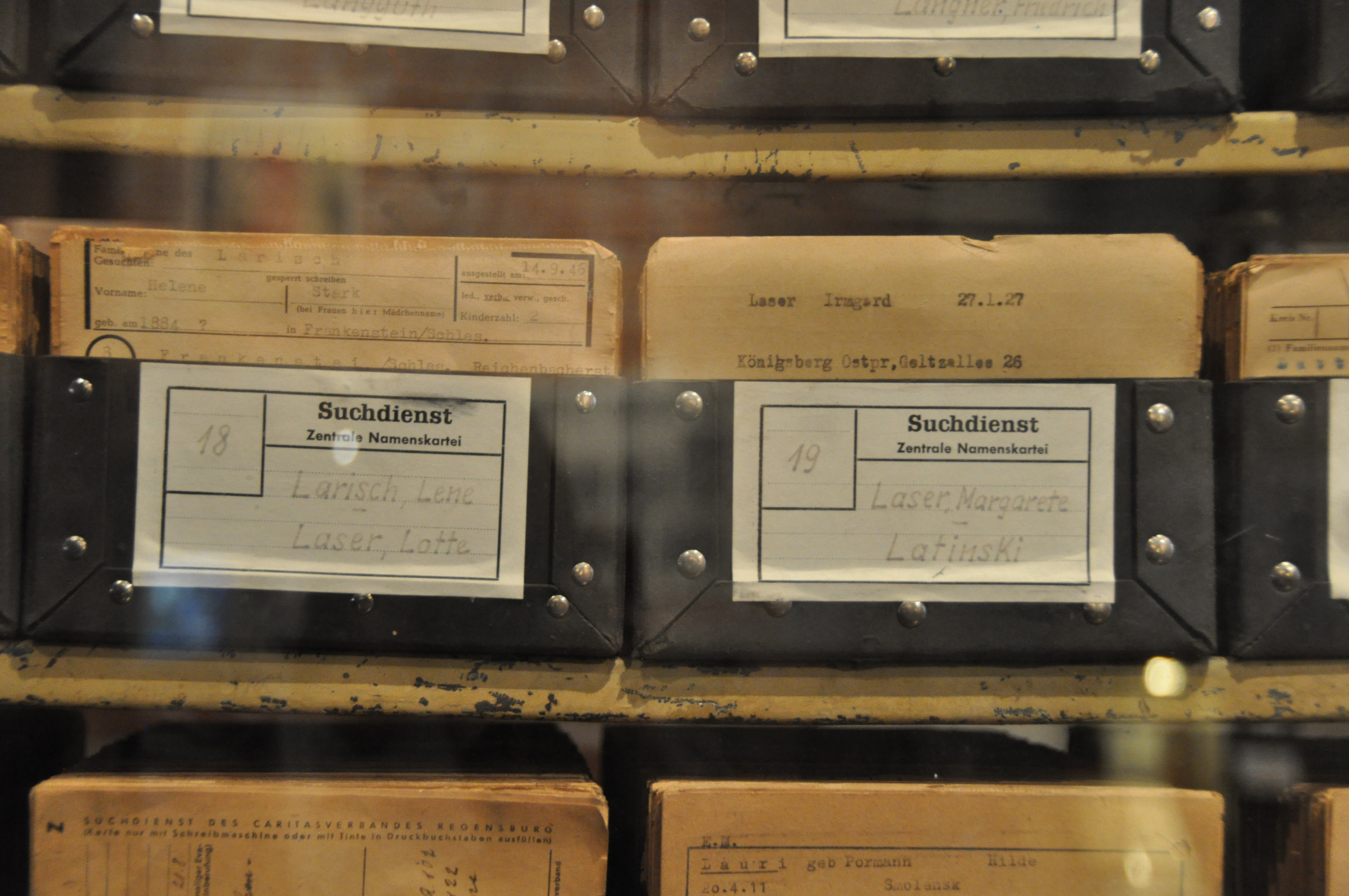

When a wandering or guardian-less child was discovered, a 15 second video-clip was made, showing the child’s face, profile and any other identifying information. These clips were played over the televisions in hopes someone would recognize their child. An identification card was also filled out for every child that was discovered and kept in the “Zentrale Namenskartei” (central name index). The museum had hundreds of these small boxes of ID cards, stacked higher than your head. Nowadays, this system seems almost un-workable, totally archaic, but remarkably, over 7 million families were reunited using this system. 7 million!! It was mind-boggling to think about how many families were ripped apart because of war, despite 7 million successful reunions.

That’s it for this road trip!